Yes, It does turns me on... Wanna feel it...

Minute Understanding of Sound In Creation

Friday, January 16, 2004

Mridangam Language

One might assume, therefore, that one could assign a MIDI note for each syllable, and then use a mridangam sample of each syllable to play back these solkattu compositions. However, there is considerable flexibility in the system of interpreting the solkattu for the drums. For example, the syllable ta is used for 11 different strokes. Over the years, the solkattu system has evolved to serve as a structure for many different drums, and so many different interpretations are possible.

Playing Technique

| The fingering technique is a very important consideration in a discussion pertaining to mridangam. The mridangam has a balance between the powerful and delicate techniques. A brief look at the history of the instrument shows why. |

Mridangam - History

| The origin of mridangam goes back to the Indian mythologies wherein it is stated that Lord Nandi (the Bull God), who was the escort of Lord Shiva was a master percussionist and used to play the mridangam during the performance of the " Taandav " dance by Lord Shiva. Another myth adds that that the mridangam apparently was created because an instrument was needed that could recreate the sound of Indra (the Hindu counterpart of Zeus king of Gods) as he moved through the heavens on his elephant Airavata. That is why mridangam is called the 'Deva Vaadyam' or the instrument of the Lords. |

Mridangam

| The mridangam is the classical double sided drum of South India and is used as an accompaniment for vocal, instrumental and dance performances. The term mridangam is derived from the sanskrit words "Mrid Ang" which literally means "Clay-Body," indicating that it was originally made of clay. |

Music Expressions

As is the case with most other systems of the world, Carnatic music also uses the human voice as well as several instruments of both Indian and Western origin. As already stated in the introductory section, there is an amazing open-mindedness when in comes to adopting good things from other systems. Several instruments like the violin, mandolin, guitar and the saxophone have been adopted successfully, of course, with a few modifications to suit the requirements of Carnatic music.

Of the innumerable instruments developed by man, very few can match the most natural instrument - the voice. Carnatic music gives pride of place to Vocal music. This is because vocal music has the added dimension of lyrics, which is one of the basic components of Carnatic music. A vocalist can project the lyrics and the theme of the music the best. Even the melody instruments try to approximate to vocal standards. Hence, a student interested in instrumental music career generally learns vocal first and then repeats the music on the instrument.

Singing can be defined as the musical expression of feeling through the medium of vocal organs and the organs of speech. The technique of voice production for singing is more complex than it is for speech, as this requires the control of three sets of muscles - inspiration and expiration (respiratory muscles), phonation (intra and extra-laryngeal muscles) and those of articulation (muscles of tongue, jaw, lips and soft palate).

A Carnatic vocalist is expected to possess a voice that is rich in tone and volume, has depth and is capable of sustaining different notes for a long periods without any wobble. He/she must also possess a range of at least two and a half octaves and execute with clarity and verve, phrases of different tempo. The various embellishments or ornamentations (gamakas) and tonal shades should be aptly produced for rendering different types of musical compositions and other creative aspects of Carnatic music. The technical exercises and compositions of Carnatic music are designed to impart all the above. Of course, the student must have the right attitude, technical guidance and perseverance!

Artist's Task

On Nov. 18, 1995, Itzhak Perlman, the violinist, came onstage to give a concert at Avery Fisher Hall at LincolnCenter in New York City. If you have ever been to a Perlmanconcert, you know that getting on stage is no smallachievement for him. He was stricken with polio as a child,and so he has braces on both legs and walks with the aid oftwo crutches. To see him walk across the stage one step ata time, painfully and slowly, is an unforgettable sight. Hewalks painfully, yet majestically, until he reaches his chair.Then he sits down, slowly, puts his crutches on the floor,undoes the clasps on his legs, tucks one foot back andextends the other foot forward. Then he bends down andpicks up the violin, puts it under his chin, nods to theconductor and proceeds to play. By now, the audience isused to this ritual. They sit quietly while he makes hisway across the stage to his chair. They remain reverentlysilent while he undoes the clasps on his legs.

They wait until he is ready to play.

But this time, something went wrong. Just as he finishedthe first few bars, one of the strings on his violin broke.You could hear it snap - it went off like gunfire across theroom. There was no mistaking what that sound meant. Therewas no mistaking what he had to do. People who were therethat night thought to themselves: We figured that he wouldhave to get up, put on the clasps again, pick up the crutchesand limp his way off stage, to either find another violin orelse find another string for this one. But he didn't.

Instead, he waited a moment, closed his eyes and thensignaled the conductor to begin again. The orchestra began,and he played from where he had left off. And he played withsuch passion and such power and such purity as we had neverheard before. Of course, anyone knows that it is impossibleto play a symphonic work with just three strings. I know that,and you know that, but that night Itzhak Perlman refused toacknowledge that. You could see him modulating, changing,recomposing the piece in his head. At one point, it soundedlike he was de-tuning the strings to get new sounds from themthat they had never made before.

When he finished, there was an awesome silence in the room.And then people rose and cheered. There was an extraordinaryoutburst of applause from every corner of the auditorium. Wewere all on our feet, screaming and cheering, doing everythingwe could to show how much we appreciated what he had done.He smiled, wiped the sweat from this brow, raised his bow toquiet us, and then he said, not boastfully but in a quiet,pensive, reverent tone, "You know, sometimes it is the artist's task to find out howmuch music you can still make with what you have left."

What a powerful line that is. It has stayed in my mind eversince I heard it. And who knows? Perhaps that is the way oflife - not just for artists but for all of us. So, perhapsour task in this shaky, fast-changing, bewildering world inwhich we live is to make music, at first with all that wehave and then, when that is no longer possible, to still makemusic with all that we have left.

Thursday, January 15, 2004

The Sounds of Silence

The first performance of John Cage's 4'33" created a scandal. Written in 1952, it is Cage's most notorious composition, his so-called "silent piece". The piece consists of four minutes and thirty-three seconds in which the performer plays nothing. At the premiere some listeners were unaware that they had heard anything at all. It was first performed by the young pianist David Tudor at Woodstock, New York, on August 29, 1952, for an audience supporting the Benefit Artists Welfare Fund -- an audience that supported contemporary art. More Details>>

Sunday, January 11, 2004

Full of Jargon

|

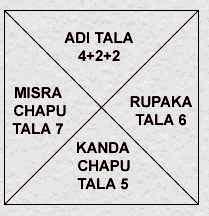

Percussion, Rhythm, and TaaLam

KaLai & EDuppu

Another term is kaLai, which refers to using multiple beats in one beat. Thus 2nd kaLai of aadi taaLam will use 2 beats for every one beat of the taaLam. This is noticeable in the speed of the song and the length of the aavartanam (cycle of the taaLam).

EDuppuIn some cases, the taaLam doesn't "begin" on the beginning of the first beat (called the samam). It may begin just 1/2 beat before or after, or 1 1/2 beat after, for example. The place where a particular section of a song (anupallavi, pallavi, or charaNam) begins in the taaLam is called the graham or eDuppu.

m u s i c

Minute Understanding Of Sound In Creation

An equally interesting exercise - think of five songs you really like. Can you explain why you like them or what is in common with all of them ? Can you 'explain' and define your musical taste ? Unfortunately, however much analysis one does, in terms of frequencies and so forth, it finally boils down to psychological factors when it comes to music and taste. Analysis is merely a tool to understand some of its structure. It can never explain why some musical sounds are deemed 'romantic' or 'harsh' or why some ragam is an evening ragam (if you believe in such things). Such mystique about music will come back to haunt us and will forever prevent us from understanding its totality in an objective manner.

Marga & Chanda Talams

1 Guru - 1 beat and counting 7 fingers

1 Plutham - 1 beat, 1 krshyai & 1 sarpini

1 Kakapadam - 1 beat, 1 krshyai, 1 sarpini & 1 pathakam

1 krshyai - waving the hand towards left, it has 4 aksharams

1 sarpini - waving the hand towards right, it has 4 aksharams

1 pathakam - raising the hand vertically, has 4 aksharams

These talas are complicated and are found in very few compositions. In fact, the music of Tamils in ancient times had complicated rythm patterns like Chandha talam. Rythm was given importance. The Thiruppugazh is a classic example of the variety and complex nature of tala pattern in Carnatic music. The uniqueness of this tala lies in the fact that it varies according to the stress and rhyme-patterns (called Chanda) in the Tiruppugazh.

An example of a tala that uses all the units mentioned so far is Simhanandana tala, the longest tala, with 128 units.

Anaagatha - Atheetha

There is another aspect of taalam which merits attention - the starting point of the song in relation to the taalam or the eduppu as it is called. Many songs start simultaneously with the beat and this is termed as sama eduppu indicating that the start is level with the taalam. Often, the song starts after the taalam is started, leaving an empty rhythm pattern at the beginning. This gap allows the singer and the instrumentalist a greater freedom in improvisation. This is indicated by the term anaagatha eduppu. Sometimes, the song starts before the beat and this is termed atheetha eduppu. This construction is often used to add a one or two syllable prefix (eg. Hari, Sri, Amba) to the text of the melodic line. A peculiar eduppu is associated with a taalam called Desadi taalam. Though this taalam actually consists of four movements, each of two aksharam duration, it is customary to keep pace for this taalam using simple Aadi taalam. Then, the eduppu is at one and half aksharams from the start of the taalam or three eighths way into the laghu. An example for Desadi eduppu is the song 'Bantu reethi kolu iya vayya Raama' in the ragam Hamsanaadham.

Prominent Talas

|

Its 175 now ;-)

We know that the Chaturasra Jaati Dhruva tala has an external count of 14. However, while rendering the tala, how are we to ensure that the time-interval between each beat is uniform? This is where we introduce Gati. Now, we could have a fixed interval of 4, 3, 7, 5 or 9 counts between each beat. Let's take the example of Chaturasra Jaati dhruva tala with an interval of 4 units per beat, i.e. Chaturasra gati. The external count of 14 is multiplied by 4 (gati units) and we get a total of 56 internal counts for the tala. The same would change to 42 in Tisra Gati (14*3). In other words, each of the 35 talas can be rendered in any of the 5 different gatis. Thus the 35-talas become 175 (35*5).

Yet another Jargon - Gati

The important thing to remember here is that the common names for the types of Jaati and Gati are only indicators of the values 4, 3, 7, 5 and 9. Whereas Jaati refers to the external finger-counting, Gati refers to the internal count between beats in the tala-cycle. Jaati gives a structure to the tala and Gati determines the gait of the tala.

How come 35 Taalas then?

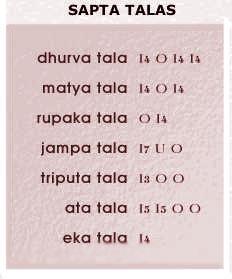

Saptha Talas

|

The Tala System

There are six parts (Angas - limbs) of a tala but the following three are used more frequently:

U - Anudrutham, A beat, represented by the symbol "U". This is physically represented as 1 unit

0 - Drutham, A beat and a wave of the hand, represented by the symbol "O". This is physically represented as 2 Unit.

| - Laghu, A beat followed by finger counts starting from the little finger. It is represented by the symbol "l". Laghu can be of five types (Jaati) depending on the number of units.

Units

Chaturasra (Jaati) laghu has a beat plus 3 finger counts, which is a total of 4 units.

Tisra (Jaati) laghu has 3 units i.e. a beat plus 2 finger counts.

Misra (Jaati) laghu has 7 units, i.e. a beat plus six finger counts.

Khanda (Jaati) laghu has 5 units, i.e. a beat plus four finger counts.

Sankeerna (Jaati) laghu has 9 units, i.e. beat plus eight finger counts.

Rhythmic Aspects

Tala and Laya

Tala is often confused with Laya. Laya refers to the inherent rhythm in anything. Irrespective of whether it is demonstrated or not, it is always present. This can be better illustrated with an example. We know that the sun, the planets and other heavenly bodies are moving objects. Even as our earth rotates on its axis and revolves around the sun, these bodies have their own fixed movements and speeds. Even a microscopic disturbance in that speed may lead to disasters of huge proportions. So laya can be explained as the primordial orderliness of movements. Expression of laya in an organised fashion through fixed time cycles is known as Tala. Thus it serves as the structured rhythmic meter to measure musical time-intervals. Tala in Carnatic music is usually expressed physically by the musician through accented beats and unaccented finger counts or a wave of the hand. In other words, Tala is but a mere scale taken for the sake of convenience.

The present day mridangam is made of a single block of wood. It is made either of Jackwood or Redwood. Jackwood has more fibrous structure than the other types of wood.The packing of the fibres is also very high.The pores present in jackwood is less when compared to others. The pore size and distribution of the material can be inversely proportional to the modulus of the wood.the density of jackwood is also less when compared to other woods.

The present day mridangam is made of a single block of wood. It is made either of Jackwood or Redwood. Jackwood has more fibrous structure than the other types of wood.The packing of the fibres is also very high.The pores present in jackwood is less when compared to others. The pore size and distribution of the material can be inversely proportional to the modulus of the wood.the density of jackwood is also less when compared to other woods.